The Kipsigis are uniquely recognized as one of the many Kalenjin dialects in Kenya. The Kipsigis speak the Kipsigis language, which is more or less like the Nandi dialect but smoother. The name Kipsigis is derived from the term ‘sigiisyeet’ which means giving birth.

Origin and Migration

The Kipsigis are said to have migrated from the North through South Sudan into Kenya. They traveled southwards in the 19th Century and settled in the Rift Valley.

They continued their journey to the south raiding villages for cattle and grazing land. Finally, they settled in the now Kericho county, having displaced the Kisii, Luo, and Maasai. This explains why the displaced tribes are now neighbors of the Kipsigis to the west and south.

Demography

There has been a vast population increase of the Kipsigis people since the 1950s. Their current population is said to be of more significant number than other Kalenjin dialects. The latest census estimated Kalenjins at 6.5 million people.

The Kipsigis are primarily found in rural areas where they practice agriculture on large farms. Very few live in urban towns.

Clans

In the Kipsigis society, a clan comprises families tracing their lineage through a shared male ancestor, making its members blood relatives with a paternal ancestry connection.

These clans and their subdivisions have specific signs and symbols known as totems, which include animals, insects, or celestial objects like the sun, for identification purposes.

Here are the clans and their particular totems among the Kipsigis:

- Kabarsumek – Moset

- Kapkomosik – Moset

- Kaboboek – Moset

- Kabarangwek – Beliot

- Kamorosek – Beliot

- Kibasisek – Asista

- Kibindoek – Soet

- Kabioria – Kimaketiet

- Kapkechwoek – Mororochet

- Kapkomutget – Ngetundo

- Narachek – Chesireret

- Kipchililek – Beliot

- Motoborik – Kimaketiet

- Kabecherek – Moset

- Kipgoitim – Beliot

- Kapchepkitwaek – Kongonyot

- Kipkendeek – Sekemiat

- Kipkigitek – Ngiri

- Kipsirgoek – Ngirii

- Cheptalamek/Kapcheplel – Cheptalamiat

- Kibetuk – Kimaketiet

- Kamanereriek – Kimaketiet

- Kiplekenek – Cheplanget

- Kapkaon – Kongonyot

- Kapkerichek – Kongonyot

- Kapkolwolek – Beliot

- Kaptirikwek – Beliot

- Kipgogosek – Chepkogosiot

- Kibomuek – Cheptirgichet

- Kamasega – Ngetundo

- Kamago – Ngetundo

- Kibaek – Mororochet

- Kapngererek – Kongonyot

- Chekimueek – Ngetundo

- Kabargesaek – Birechot

- Kspchamakondek – Kongonyot

- Kapsegiit – Ngokto

- Kipsamaek

- Boswetek – Moswetit

- Kapmososwoek – Kongonyot

- Kapchepkewel – Ilet

- Kamoek – Kongonyot

- Kipkelesek – Ngetundo

- Kapsosomek

- Kapkitolek – Ngetundo

- Kibororek – Lelwot

- Kamochoek – Soet

- Babasik – Laitiko

- Kapkolwolek – Belio

- Kapchebokolwol

- Kamarusek

- Kapcheroigek – Tisiet

- Kaptuiek – Ngetundo

- Kapmalummabwai

- Kapchemangalek/Kapchepkersut – Kongonyot

- Kipsamaek – Ngetundo

- Kapsengerek – Moset

Age sets

Historically, the Kipsigis had seven cyclical age sets or ibinwek. The age sets include:

- Nyongi

- Maina

- Sawe

- Chumo

- Korongoro

- Kaplelach

- Kipnyige

Food and Economy

Due to the highlands that experience abundant rainfall, the Kipsigis are known farmers. They keep dairy cattle and plant cash crops like tea, coffee, maize, beans, vegetables, and millet.

Traditionally, the Kipsigis tilled their land and cultivated it using available tools like ‘morut’ which was a blade made of iron. Now, a vast area of land can be cultivated due to new technology.

They were also traders. They carried out barter trade to supplement their produce. Cowry shells were used as currency to buy agricultural produce in other situations.

Culture

Amongst the Kalenjin, initiation was a fundamental form of passage. Kipsigis men identified themselves with a particular age group according to the time they got circumcised. They would then call each other ‘Bakule’; consequently, a bond is created, linking them as blood brothers.

The Kipsigis used to name their children by ancestral reincarnation, but they later dropped the practice after the missionaries convinced them it was evil.

According to the Kipsigis, boys, and girls were named by the “Kip-” and “Chep-” names, mainly the second names. Traditionally, Kipsigis girls were circumcised. Girls who were initiated were given names with the “Tab-“but since female circumcision has over time been abolished, it has wholly led to its loss.

Young men already circumcised are given the “Arap-“naming system as their surname.

Symbols of Social Organization

Here are the symbols of social organization for the Kipsigis community.

The Orkoiyot

The Orkoiyot tradition was brought to the Kipsigis in 1890 after the assassination of Kimnyole Arap Turgat.

Kimnyole sent his three sons (Kipchomber Arap Koilege, Arap Boisyo, and Arap Buigut) to Kipsigis, who immediately began instituting a Kipsigis merger, each establishing imperial homesteads.

Em/emet

This was the topmost recognized geographic partition among the Kipsigis. It covers a restricted geopolitical region as a jurisdiction of the Kipsigis entitled to definitive self-government. To the Kipsigis, this unit was a political body.

Kokwet

This was a Kipsigis territorial unit. Kokwet is derived from the term ‘kok,’ which means a place in front of a man’s house where adults meet, sit, and eat together.

Many ‘Kokwet’ resulted in ‘kokwetinwek,’ and they were mostly demarcated by physical features such as rivers, streams, valleys, or even in some instances, fences.

The Kook

Traditionally, the old and the rich were respected more in the community. Among the Kipsigis, village elders were given positions to the old, the retired military men, and the rich.

The ‘kook’ (village elder) was believed to have wisdom enough to pass judgment and deliberate on the matters affecting the community.

Tribal Wars

The Maasai and the Kipsigis have historically alienated each other right from a period earlier than the Maasai era. This was usually evident in cattle raids, eventual battles, and fleeing the Maasai. Another known feud was between the Kipsigis and the Kisii.

Gender Roles and Status

Kipsigis women were stay-at-home wives. They took care of the children and did house chores. They also made baskets (Kerebet) for storing flour and porridge. The baskets were also used to conserve flour from spoiling.

They prepared meals, collected water and firewood, tended the gardens, grew small millet and sorghum, and took care of children.

The men cleared land for cultivation, repaired fences, built houses, hunted, and cared for domestic animals. Kalenjin men are perceived to be very reserved people who find it odd to help in chores meant for women.

Religious Beliefs, Rituals, and Holy Places

The Kipsigis believed in a supreme being called Asis, meaning Sun.

Older men in the community carried out crucial religious functions. They would chant prayers and even speak words of blessing upon the people.

Besides offering their prayers to Asis, the Kipsigis had holy and sacred places. The ‘kapkoros’ was a shrine used as a place of worship. The shrines were in particular places which were considered holy and sacred.

A more miniature replica of the ‘Kapkoros’ shrine ‘mabwayta’ was used as a family altar. This is where individual families would gather to pray.

Death Rites

While other African communities saw death as a rite of passage, the Kipsigis had mixed feelings about what to presume after a person dies. To them, death was tragic, and the deceased would be buried facing the west. Other instances involved the dead being put in the forest and left to decay or eaten by wild animals.

Marriage

The marriage process was paramount in the Kipsigis community and entailed several ceremonies before the bride could enter her husband’s home.

The ‘koito’ was preceded by events where the groom’s father would visit the bride’s home dressed in a particular attire (a robe made of monkey fur).

He then makes his presence known by leaving a walking stick before the bride’s family altar (mabwaita). This signified that he had put forward a marriage proposal. After that, the two fathers set a date for the next visit.

On the next visit, close relatives of the groom and some of his agemates, referred to as ‘bakules’ were sent to the bride’s home to present cattle which in most cases comprised of ox, goats, and cows.

The two parties then sat down to deliberate on the clan, kinship, and cultural hurdles. After these factors are straightened out, the groom’s father returns with a cow (‘teet-aap ko).

By this time, the bride’s father would have done his investigations and had his final say. If he gives the go-ahead, the bride’s family will welcome and anoint the visitors with special butter, which signifies blessings.

A feast is prepared, and the bride’s parents would inquire about the number of cattle the groom had. They would then reach an agreement, and if the groom could surpass the number of cattle agreed on, the bride would be considered lucky and more loved. A ceremony where the cows are meant for the bride price is pointed out. A special stick, ‘noogirweet’ is used to identify the cows.

The wedding is then set to take place. The bride’s family gets invited to the groom’s home, and the bride is sent to the following day.

More so, the Kipsigis had other forms of marriage that were practiced. Like any other African society, there were instances where marriage was by betrothal. Girls and boys were identified at a tender age, and when they were mature, they would be married.

Another situation was when a girl ran away to be married. This happens when both the man and woman suspected that the parents were against their being together or in other situations if the groom was poor or of low status in the community and could not afford the bride price.

In some cases, if a woman was married and unable to bear children for his husband, she was allowed to marry another woman who would then get children for her.

Magic and Witchcraft

Traditionally, African communities believed in witchcraft and magic. Witches and magicians were able to cure disease. In some instances, they unveiled their magic to curse.

However, among the Kipsigis, omen readers, witches, and magicians were loathed. They were outcasts in the community. Witches were women and exceptional occasions, men.

Another powerful being among the Kipsigis was the Orkoiyot. Although they benefitted the community well, they were still considered outcasts. They could foresee the future, heal and read omens. The Orkoiyot were members of the Talai clan.

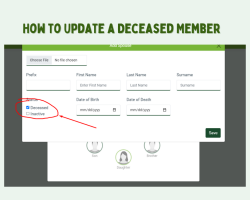

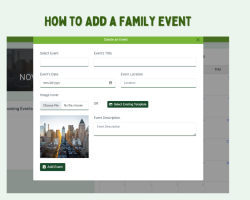

Do you love culture?

Would you love to preserve your family stories?

Sign up on the Oret website to create your family tree and preserve your history.

Share this Post