The Keiyo people are an ethnic group residing primarily in the Elgeyo-Marakwet County of Kenya. They are part of the larger Kalenjin community, which includes several other subgroups.

Here’s a summary of the Keiyo people.

Origin of Keiyo

It’s asserted that the term Keiyo came to be because Nandi women who were sterile conceived when they migrated to Keiyoland (Kip-Keiiyo – a place where one goes to give birth).

Another myth on how the name came to be is associated with the Maasai people. They inhabited the Uasin Gishu Plateau in the 18th and 19th centuries. They termed the inhabitants of the Kerio floor the “Il-Keyu.” Swahili traders later tainted this name to read Elgeyo.

History

Keiyo, part of the Kalenjin ethnic group, is believed to trace its ancestry to a forefather, Kole, who lived around Mt. Elgon (i.e., Tolwop Kony). After moving southwards along valleys and a wide river (believed to be River Nile), the man had five sons, and his first son was named Chemng’olin, who moved from the original with the aim of ‘kondi’, i.e. to inherit and conquer.

The second son preferred the task of reproduction -Kosigis- meaning to “reproduce”. This is the Kipsigis sub-tribe. The third son wanted to go out and practice milking, thus the name Keiyo, later revered by the Keiyo. The fourth son wanted to break off from his father and collect termites, as there was a severe drought then.

The process entailed the ground’s pocking (‘ketugen’) for the termites to come out from the ground. The son said he is going ‘ this side’ (kamase) and hence the present Kamasia or the Tugen. The fifth son chose to remain in the ancestral home and stay Kong-Kony’, ‘meaning to stay rooted’.

Colonial Times

The Keiyo has had a long interaction with British officials and the government. The colonial government had constant conflicts with the Keiyo.

The Keiyo raided cattle belonging to the British, and as a result, a row developed that led to the death of several people by the British government. This feud began when the hut tax was imposed, and the Keiyo were banned from grazing on the farms bordering the British reserve.

Land Utilization

The Elgeiyo People divided their land into territories to control intermarriage and displacement of a clan by other clans. Totems were given to identify the clans.

From the south to the north the territories are Metkei, Kapkwoni, Maoi, Samich, Kipkingwo, Kapsiro, Tumeiyo, Sego, Epke, Chang’ach, Kowochi, Mwen, Choop, Morop, Kapchemutwa, Rokocho, Maam, Irong’, Kaptany, and Mutei. A series of stones known as Koiwek were used to mark the divided land.

Clans

The Keiyo is distinguished into sixteen clans. These are:

- Talai

- Terik

- Tungo

- Toiyoi

- Targok

- Kimoi

- Kong’ato

- Kabon

- Kabilo

- Soti

- Saniak

- Siokwei

- Sokome

- Kure

- Mokio

- Mokich

Food and Economic Activities

In the eighteenth century, the Keiyo clans were hunters and gatherers. Later on, in the nineteenth century, they become agro-pastoralists. They practiced cattle rearing and cultivation. They also hunted animals like antelopes, buffalos, and wild pigs for meat.

With the acquisition of livestock, their food type was enhanced. Milk, blood, and meat became a new diet to the Keiyo Community.

The basic unit of production and consumption was the individual family ( a man, his children, and his wives). Barter trade was the main form of trading by the Keiyo since the money economy was non-existent. For example, the Keiyo women sold a pot for the amount of grain it would hold.

Social Organization

Traditionally, the Keiyo community was centered on family, lineage, clan, and age groups. The families were both nuclear and extended. This affected marriage, ceremonies, and land ownership.

A lineage, bikab oret was a group of people linked by descent from a common ancestor, usually in the male line. Clans, oret, were also based on descent from a common ancestor but were larger than lineages and went back further in time. Lineages were the starting point for new clans.

Through intermarriages, initiation ceremonies, and symbiotic relationships, families and clans could build an extensive network of alliances and relationships that was a principal factor in consolidating the once fragmented society.

Each family, lineage, and clan had its role within the pre-colonial Keiyo society’s social structure. In addition, each man was also a member of an age or generation group in the community.

Governance System

For the Keiyo, society was egalitarian. They believed in equality and that people deserved equal rights. Disputes and other social conflicts were settled by the council of elders of the ‘Kokwet’ (clan).

The council deliberated on issues like cattle raiding, the time of initiation ceremonies, the approach of wild animals, and on any other calamity in the society, such as strange disease, drought, and the appeasement of Chebo Kipkoiyo (the name for God).

Keiyo Dialects

There are four predominant sub-dialects of the Keiyo dialect. These are Irong, Mutei, Marichor and Metkei.

Gender Roles and Status

Amongst the Keiyo, the division of labor was based on gender. Certain chores or responsibilities were considered feminine, while others required a lot of energy and strength. The men were responsible for heavy and time-consuming labor like tilling and clearing land for cultivation. Other duties done by men included herding, construction of houses, and offering security in times of war.

The Keiyo women were responsible for house chores, milking, cleaning cowsheds, harvesting, and caring for the children. On the other hand, women cooked food, milked the cows, cleaned the cowshed, harvested millet, and the general welfare of the family.

Age-Sets

The Keiyo age sets were recognized as follows; Maina, Nyongi, Kipnyikew, Korongoro, Kaplelach, Kipkoimet, Sawe, and Chuma. Men of the same age initiated together, and they lived to identify themselves with the group. This created a strong bond outside family and clan. This age set is then given responsibility and status in society.

They had a ceremony, ‘Saket ab eito’ (sharing of the bull), where responsibilities were passed from one generation set to another. Keiyo was among the many tribes that also circumcised their girls. The circumcised girls were recognized in their own age sets.

Religion and Beliefs

The Keiyo believed in God (Chebo Kipkoiyo or Cheptailel) and their ancestors ( Oiik). In addition, Asis (sun) was highly revered by the Keiyo.

The Keiyo, however, did not worship the sun. It is through the sun that they reached the Supreme God, Cheptailel. Before any rite of passage or ceremony could be performed, an elder prayed to face the east immediately after the first rays of the sun shot the ground.

They also believed that ancestors survived as spirits who would pass judgment on the community after death. There were evil spirits, chesawiloi, and benevolent spirits, oiik. When neglected, the spirits became malevolent, while those remembered through libation became benevolent.

Like the sun, ancestor spirits were not worshipped. They were expected to assist their living clan members. The general belief was that ancestors were reincarnated several times through children of the same clan. The wish of the dead relative who wanted a child to be named after them is manifested in the persistent crying of the child after birth.

On such occasions, the Keiyo would make concessions to God through appeasement ceremonies and sacrifice. The most popular was the Biret ab Seek (splitting of water) ceremony intended to cleanse the society of all evils committed. The Kerio river was always an ideal choice.

This appeasement was a monopoly of men. Men would offer sacrifices around a thick bush called kapkoros (public sanctuary), where an altar was constructed from a nice-smelling medicinal plant known as Nyamtutik.

The elders slaughtered A spotless white goat and roasted it on this fire. If the smoke rose to the sky at a vertical angle, it was generally believed that Asis had accepted their sacrifice.

Rituals

Lightning and thunder were viewed as a dispenser of justice. A wronged individual would personally appeal to Thunder (ilat) to get revenge on his behalf.

When there was a drought, the women of the Toiyoi clan whose totem was rain were requested by Keiyo elders to intercede on their behalf. The Kaptoromo and Kaplegek families were respected for possessing ritual powers to forecast the future and ‘make’ rainfall.

Another crucial role played by religion among the Keiyo was the arbitration of disputes. Self-explicatory oaths settled disputes that neither the elders nor the Kokwet could solve. Among these were swearing by thunder, ilat, stripping naked at a public forum, or licking the soil.

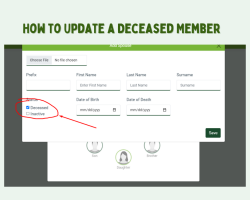

Do you love culture? Would you love to preserve your family stories? Sign up on the Oret website to create your family tree and preserve your history.

Share this Post